We were on one of two airplanes to arrive in Nairobi at around 9 p.m. Everyone was funneled into a mass waiting area that eventually led to cordoned off lines and Customs Clerks. There was no clear indication of which line you should get into but it was not a problem. Outside of the Diplomatic queue, everyone was expected to find her / his way to any desk. There, each person had to stand in front of a camera, some were totally fingerprinted, some were partially fingerprinted, and I was not printed at all.

Outside of the building, we looked for the person who was sent to meet us but saw no one. Someone suggested that we look around the corner where they said the drivers must wait. Sure enough, in the darkness of the parking lot, there were more than a hundred persons lined up along a sidewalk. They were holding small signs, waiting quietly and saying nothing. To maintain order, this was what the authorities permitted. It was a strange, unexpected and welcoming sight. Daniel and I passed through twice before seeing our names on a paper held up by one of the Kisii University Students sent to fetch us. We had already been travelling over thirty hours when the plane landed. Tired and sweating, I was working to decipher this late night welcome to Kenya. About twenty students had come along to greet the international arrivals. We joined the rest of the group on the sidewalk of the pick-up area to wait for the bus and until all of the incoming poets had arrived. There were more waits as Students were dropped off at the places where they might stay overnight and finally we checked in at the hotel around two a.m. Several of us needed to decompress and instead of going straight to the shower and to sleep, we assembled in the 24-hour hotel restaurant to eat and to talk. This late night meeting fell into a pattern of stolen moments where we, as internationally based poets haunting various time zones, met at day’s end to unwind outside of the moving feast of the Kisii University bus.

Our welcome to Kenya was a complete cultural experience in itself and to re-think it is to slip back into the exhaustion of that first night in Nairobi, and the challenge of remembering each of the Students’ Kiswahili and English names. As the days progressed and we went out on field trips, read our poems, listened to poems, songs and saw dances of more students and other local people, I realized that the closeness of the personal encounters might not be remembered with names attached. The cultural exchanges, the faces and personalities of those I met only once, or only a few times remain committed to memory and to a wish of returning for a longer stay at sometime in the future.

Monday, Oct. 3 – bus ride from Nairobi to Kisii, arrival: at Kisii Dans Hotel around midnight. Throughout the Festival, there was a lot of assembling at the Kisii University bus. Our driver, David waited patiently for minutes and hours to drive us through city traffic and over highways. When I asked him how many hours he worked everyday, he said twelve and added that if he got a good three hours of sleep a day, he was fine. We saw him maneuver through many tricky passages and he always kept his cool!

During the trip over mountains to arrive in Kisii, we made three short stops; to purchase and sample fire roasted corn, to throw the remaining corn husks to a family of baboons who waited along the highway to catch a meal, and at a market / rest area with snack foods and washrooms.

Oct. 3 – 8

Co-presentation portions of essay: FLOW: BIG WATERS as published in the billie magazine and poetry from the Everglades project (2014-2016). After the first day of presentations, I read other poetry and short stories. The schedule was changed and augmented as the days progressed. No one seemed to mind as we all had chances to read and the days stretched out longer to accommodate all of the voices we needed to hear, and to attend events that we needed were scheduled to participate in.

Other poetry readings took place on the Kisii University Campus, at the Genesis Primary Preparatory School, the St. Charles Kabeo High School and at the legendary Lake Victoria, headwaters of the White Nile. On the way to and from Lake Victoria, we passed not far from the region of Kogelo. This small village is garnering attention as it the ancestral home of Barack Obama’s father. Along the highway, we saw businesses with names that wish to identify with America – The Whitehouse Café, The Pentagon, and etc.

The Kistrech Poetry Festival was held during the Kisii University Cultural Week. On one occasion, there were some poetry readings from our group and demonstrations of various tribal songs and dances before the rains, common to this time of year, necessitated an end to the afternoon’s festivities. This was after we had the chance to see a group of Maasai nomad warriors, in red robes, perform with their staffs. The group is one of the many tribes represented in the Kisii University Student body. The view was spectacular and historic as we sat and stood in the tents surrounded by high Kisii mountain backdrops. Later that day we were treated to a special dinner at the invitation of Professor John S. Akama, Vice-Chancellor of Kisii University.

Our group, the internationally based poets from the Kistrech Poetry Festival, and Kenyan Students from the University of Kisii and Nairobi, also visited the Bogiakumu Village. We were welcomed individually into homes to learn something of the lifestyle of villagers and to talk to the families about our own countries. The home of the two women I visited was started in 2014 and is still under construction. It is a wood frame and mud construction, a very sound construction base for the area. Many villagers now forego thatched roof construction in favor of galvanized corrugated steel. This was the case of the home I visited. The most important factor is that a generous overhang guarantees that the walls stay firm and dry during the rainy season. Seeing the roof of this home made me think of the problems that skimpy roof overhangs sometimes cause in Canada.

The woman and her daughter-in-law were introduced as the owners of the home but they were not named. They showed me some of the corn crop they were drying to be ground for flour and told me that this is their only source of flour. Two Kisii Students, Mandolin and Ombui had come along to interpret anything that was not understood and everyone took part in the conversation. The women cut sugar cane growing outside of the door and we all sat chewing the cane while talking. Everyone told me that it is good for the teeth.

Oct. 9 – 10

The return trip started with a nine-hour bus ride back from Kisii to Nairobi. Usually just six hours, the ride was extended due to traffic jams on the mountain roads and in Nairobi itself. Overnight at the Nairobi hotel gave Daniel and I the chance to get a good rest before starting the pattern of long airport waits and long flights to get back home. Students Elly and Justus accompanied us on the return bus trip. It was then that I realized how much shepherding those Student Ambassadors had done for us during the festival events. There was always someone looking out for us, explaining things and introducing each of the poets with great enthusiasm.

Since returning to Canada I noticed on one news website that the Student population in Kisii is largely made up of young people commuting from rural areas. It comes as a surprise to me as they all seemed to be well informed and they project an urban image in their adaptability and manner of dressing. One thing that seems sure is that these Students worked hard to keep up with the schedule that we followed during the Festival while also commuting and studying.

Stray Observations

According to the nature of travel and its unexpected paths, participating in the Kistrech Poetry Festival, Kisii, Kenya was not something that I could ever have imagined. Even today as I look through the Festival magazine, I see images that reveal only the smallest sense of the close cultural exchanges that the event sponsored. Everything seemed to differ from the North American experience.

Throughout Kenya, many places are under construction and in Kisii, they are building more high rises. We noticed that some cement foundations looked porous and hastily constructed. One schoolteacher told us that the city is on a fault line and that there is some concern about the strength of the new towers.

Televisions in the hotel restaurants play all day and there were only a few times that I listened to the TV in the hotel room. Sometimes in the morning, if there was a bit of extra time I would put it on to listen to the news, local talk shows and, surprisingly enough, African wildlife shows were always playing. Without looking, I easily recognized that low, almost whispering voice telling the story of the wild life habits of the Serengeti’s big animals.

I visited North Africa for a month during the year after I left high school. I have always taken personal offence when people refer to Africa as a whole and not as a place made up of many individual countries and alliances. Going to East Africa has made me aware of the wish expressed by many Kenyans, to be considered as part of a coalition of countries. By that, I mean that many of the people I met spoke not firstly of Kenya, but of Africa’s place in the world as a whole.

Since leaving Kenya, I have looked in on news reports of political unrest and student protests that erupted as we were leaving. Facebook posts show armed soldiers occupying those same peaceful hallways and grounds where we met and read during the Kistrech Poetry Festival. Caught in the middle, the student-poets are fighting back with words.

There was always talk of being given Kenyan names during the visit. I was surprised when, after waiting at the hotel and speaking at length with the security guards, who originally hail from Kisii; that their co-worker, the hotel clerk, also from Kisii assigned Kenyan names to both Daniel and myself. This man who was unnamed to me has called me Kwamboka – crossover. As a Writer / Artist often working in the interstice, I’ll keep this name for my return to Kenya.

The Last Airplane In The String Of Airplanes

During my travels from Moncton, NB to Nairobi, Kenya on October first and second, 2016, my expectations were suspended and they remained suspended until I returned home. After two days of travel back from East Africa on October 10, we came in on an Air Canada Beechcraft flight from Halifax in the tail end of Hurricane Matthew. Yes, the biblical reference was not lost on me as my body shook in the passenger’s seat across the aisle from Daniel and behind two big game hunters from South Africa. Daniel and I returned home from Nairobi via London and Heathrow during the throws of a rough landing in Halifax on an Air Canada fleet Boeing 767-300.

When I saw the flight listing: Halifax – Moncton, AC7762 – BEH, I could never have guessed that we would be flying in an even smaller plane than the ones that usually land on return flights from Toronto or Montréal to Moncton. That is probably because the BEH – Beechcraft is not listed on the fleet card in the pocket of information available on most planes. (and coincidentally, not on the BEH Beechcraft) In the end, our lives were lifted up in Halifax and set back down in Moncton through the coordinated skills of the Pilot and Co-Pilot, skills that we saw them demonstrate to a science as we sat mere feet from them. They tweaked each minute control on their craft while navigating paths through radar and thick clouds. Any fear I had of ‘not making it’ was suspended by the motion sickness I experienced and my fingers continued to vibrate for an hour after landing. HAIL to the Pilot and Co-Pilot who also looked greatly relieved to have landed! And yet, another shocking detail of the flight stands out more in that memory of suspended life expectancy – the first flash of the land below revealed that all of the leaves had died. They had turned from summer green to those shades of red, orange and yellow that catalogue copywriters boastfully describe as glorious. One flash and then cloud cover hid it all from view until we touched down.

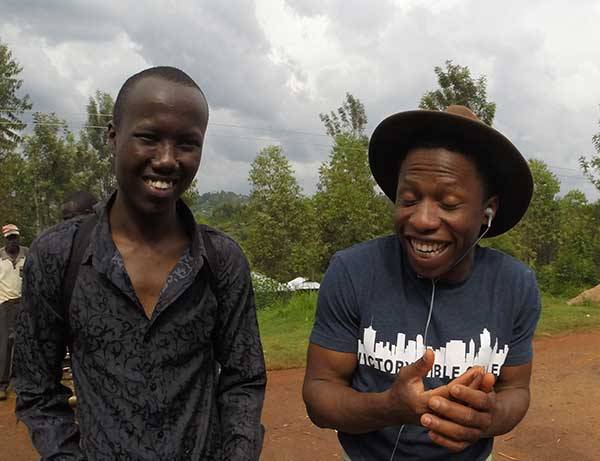

Images captions: 4th Kistrech Poetry Festival, October 3-8, 2016: Kisii University; Genesis Preparatory Primary School; Bogiamuku village; Lake Victoria; the St. Charles Kabeo High School with Beatrice Ekesa, Martin Glaz Serup, Hagar Peeters and Abel, Eric Tinsay Valles, Seth Michelson, Godspower Oboido, Erling Kittelsen, Tete Burugu, Gunnar Wærness, Sofia Eriksson, Daniel H. Dugas, Tony Mochama, Jennifer Karmin, Christopher Okemwa, Elly Omullo, Ombui Omoke, Roberto de Khalifa, Mandoline and so many others.

I would like to thank the Canada Council for the Arts and the New Brunswick Arts Board for their support. / Je remercie le Conseil des arts du Canada et le Conseil des Arts du Nouveau-Brunswick pour leur soutien.

I have participated in many poetry festivals, each series of events is unique, but the fourth Kistrech Poetry Festival had something that others don’t have. To begin, there are not many venues for international poets or artists in Africa, the economic realities of the continent dictate this scarcity of opportunities. Christopher Okemwa, the director of the festival has been working hard to create an event where the audience and the poets can share insights and discussions. Another thing that made this festival standout was the fact that our group, the invited poets and a large section of the audience, were always together. We were together in the conference room, at lunch breaks and we were together in buses travelling to different locations. This created a sense of belonging and gave us a chance to get to know each other more closely.

Most of the Festival events took place at the main campus of the Kisii University from October 3rd until October 8th with writers from Nigeria, the USA, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, Canada, and Kenya. Student participants came from both Kisii University and Nairobi University. A series of readings by internationally based, Kenyan poets as well as student poets took place on the Kisii University Campus, at the Genesis Preparatory School, the St. Charles Kabeo High School and on the shores of Lake Victoria. In addition to these, papers were also presented: Beatrice Ekesa (Nairobi University) talked about issues of globalization in the context of Spoken Word in Kenya; Martin Glaz Serup (Denmark) presented the Holocaust Museum, a conceptual post-productive witness literature that deals with the representation of Holocaust; Eric Francis Tinsay Valles (Singapore) delivered a text about trauma in poetry; Seth Michelson (USA) talked about the process of translation and the practice of human freedom; Micheal Oyoo Weche (Kenya) spoke of oral poetry and aesthetic communication practiced by children within the Luo tribe; Tony Mochama (Kenya) discussed the modernity of African poetry in Kenya; Godspower Oboido (Nigeria) compared Nigerian poet Christopher Okigbo with Russian poet Alexander Pushkin; Margaret N. Barasa (Kenya) explained the convergence of language and culture in Manguliechi’s Babuksu after-burial oratory and Valerie LeBlanc and myself (Canada) presented our poetic work created within the Everglades National Park biosphere.

This was the first time that the Festival was held during the University’s Cultural Week. The campus was alive with students and many attended the festival’s lectures and presentations. Throughout the festival, there was a constant flow of energy, of shaking hands, of being truly part of the whole, like the Festival’s program states.

Here are two key moments, two events that made an significant impression on me. Both happened on October 6rd 2016.

GENESIS PREPARATORY PRIMARY SCHOOL

We were on our way, to the Genesis Preparatory Primary School to meet and to read to the children. As with every morning, the light was intensely beautiful; the sky blue and the sun hot. At the school, three hundred children, dressed in their dark green uniforms with green and white checker shirts were waiting for us. They actually had been waiting all year for this moment and had a program of poetry, songs and dances prepared for the occasion. We all sat outside in the courtyard under the sun and under the shades of pine trees, on blue chairs and yellow chairs, on green chairs and magenta chairs. There was electricity in the air. A teacher came up front, to welcome us and invited a group of students to take place on the stage. Many students had a chance to perform poetry and to sing. To my surprise, a lot of the songs were in French. The Principal told me later that they wanted them to learn English, Kiswahili and French as many countries in the regions speak French. After that, it was our turn to read. Gunnar Wærness (Norway) created a song for a crow that was perched in a tree above us; Martin (Denmark) read 100 words from a children’s book; Jennifer Karmin (USA) involved the children with a participative poetry reading and so on.

After the readings, we were invited to plant trees on the school grounds. Poets planting trees: ‘Poet-trees’ said someone. The holes were already dug and the little seedlings were sitting in a wheel barrel, all ready to go. As each poet was busy planting, students would gather around, looking at our techniques and cheering for the forest to come. Many of the holes were sewn with yellow flowers that looked similar to squash flowers. This seemed to present a wish to protect and encourage the future growth of the trees. The man in charge of the grounds made sure that the dirt was well packed and that the seedlings were straight. When we left it looked like a little forest had been added to the valley.

BOGIAKUMU VILLAGE

When we stepped out of the bus, I don’t think any of us expected to be greeted with such enthusiasm. A musician was already playing his nyatiti, an eight-string instrument, as loud as he could. There was a lot of laughing, clapping and dancing. In the blink of an eye, we were dancing as well, which generated even more laughter. Then, each of the poets was taken in charge by one or two villagers for a personal tour. I left with my two hostesses and Cornelius, a Kisii University student who was translating the exchanges. In Kiswahili I said ‘good morning’ to the women. They both laughed. Cornelius told me that in the afternoon, the custom is to say, ‘good afternoon.’ I wished that I had a pen and a piece of paper to add this to my list of Kiswahili phrases. I repeated it in my head a few times like a mantra as we walked on the main road until we took a path down the hill. The earth is red. Everything is lush. The air is warm and humid. The pathways are incredibly complex, there are paths going everywhere. We walk past mango trees, papaya trees, banana trees, avocado trees, sugar cane and cornfields. Here and there a goat tied to a post looks at us as we go by. Cornelius tells me that the two women are widows and are cultivating their plots and raising their animals by themselves. We finally arrive at a house. As we go in, a few little chicks scramble to get out. The air inside the house is heavy and the sunlight makes the dust appear like diamonds floating in the room. The walls are covered with a lacework-like fabric. I notice two pictures on one of the walls and go to them. They are images of two smiling men. Under the images are their names and two dates. The men are dead. They are the husbands of the two women. The oldest man was born in 1963 and the younger in 1985. The images and the frames look old, as if they had been on the wall for a long time, but the younger man died just a couple of months earlier. After a while, we pull away from the wall and sit on couches. From there I can feel the heat radiating from the tin roof. Cornelius tells me that when one of the women’s husband died, she had to wait for planting the corn and this is why hers is so short compared to the rest. There is a silence. We hear the wind rustling through the nearby sugar canes. At that moment, we also feel the absence of this husband. Then the older woman gets up and goes out. We follow her lead back onto the paths. Red soil. Corn fields. The sun feels good. We arrive at the second home. The woman opens the door. The light floods into the main room. It is very hot and very bright. We sit and rest there for a while.

I can’t remember much from this house; my mind was still filled with the other place. Then we were back on the main road. There were many young people walking to the river to get water. It looked like they just came back from school. All carried yellow jugs. The river, I am told, is not far. I asked Cornelius to teach me how to say, ‘How are you’, and then I repeat this to a group of young boys. They all laugh. Cornelius tells me that there is a difference to whether you speak to one person or many. He teaches me how to say ‘how are you’ to many people, which I say many times during the walk back to the village centre.

The weather was turning. Big dark clouds were gathering and it started to rain. Instead of eating outside, we all went inside a large house to share a meal. We had yams and uji, a porridge made from ground millet. By the meal’s end, the weather had cleared up and we were invited to go back outside. We sat on plastic chairs in a big circle. The musician was in the middle with his instrument and dancers came from behind him. Eventually, it was the poets’ turn to join in the dance. Later, as we walked back through the pathways toward the bus, we saw a rainbow arching over the valley.

KISII POSTSCRIPT

The night before we left, two women were killed by the police at the market. Some people at the hotel heard what sounded like fireworks. I heard nothing. But two women died that night. Then there was a riot and wooden stands were thrown into a bonfire as people protested. In the morning as we drove down the road, the market looked empty, here and there were piles of charred wood. A few days later, the University of Kisii introduced new fee payment rules for its students. This change resulted in a massive riot, this time by students. A fourth-year woman student was shot in the head by a stray bullet, but survived. The Daily Nation (Nairobi) newspaper, reported that 10 students had been arrested while the Standard (Nairobi), mentioned that more than 30 students were arrested. According to the newspapers, the fee collection office and a School of Law office were set ablaze. Images of soldiers on the grounds of the University were unsettling to see. Many of our young poet friends from the Kisii University and University of Nairobi (Elly Omullo, Ombui Omoke, Roberto de Khalifa) wrote poignant texts on their Facebook walls, putting words to what was happening around them.

THITIMA (energy)

In this landscape

of shovelled earths

and un-shovelled earths

of arched goats

looking thoughtful

of speeding Boda-Bodas

and Boda-Boda sheds

In this land of Churches

and Choma zones

of men with shovels

walking empowered

dreaming of self-sufficiency

of yams and sweet potatoes and bananas

In this cosmology of paths

extending outward

shortcutting everything

In this endless network

of paths of life and death

of paths taken and abandoned

of paths like the energy of the Big Bang

like the music rising

from every bus

every stand

from the music

that envelops everyone

There is no stopping the going

and no stopping the rhythms.

A path goes this way

another one that way

they overlap

become larger

veer between bushes

They are the tentacles

of giant octopus’

dancing a waltz

The neurons

sending electricity

to each limb

light up this

East African night

The paths are

the way to go

the way to come

back home

They are

what is left

of having to go

of wanting to go

They are what is passed down

to the children who in turn

will invent new roads to travel upon

and new rhythms to walk along.

Daniel H. Dugas

October 9, 2016

GODS

God is everywhere!

Especially as decals on buses

GOD ALMIGHTY

in bold letters

racing on a dirt road

God in the middle of the wilderness

incarnated in every speeding Boda-Boda

God is everywhere!

I see him

in the diesel fumes of buses

I see him

in the whirlpools

of papers and bags

in the tails

of small goats

eating in ditches

I see him

in the yellow plastic jugs

balancing on heads

I see him in the tarps

flapping in the wind

in the wind that controls everything

I see him

in the smoke of every fire

of this never ending choma zone

He is here,

everywhere,

present on each kernel of corn.

Daniel H. Dugas

Oct 10, 2016

*

I would like to thank the Canada Council for the Arts and the New Brunswick Arts Board for their support. / Je remercie le Conseil des arts du Canada et le Conseil des Arts du Nouveau-Brunswick pour leur soutien.